A fitting place to go on Liberation Day in Italy is the small hamlet of Sant’ Anna di Stazzema.

On an August morning in 1944, German troops entered Sant’Anna di Stazzema and committed what is probably the worst war crime on Italian soil, executing all people present that day in the hamlet, then killing the animals and burning the village.

The able-bodied adult men of the village were hiding further in the mountains, while the women, children, and elderly in the village believed themselves to be safe. Yet they were rounded up, all 560 of them, and systematically executed.

This was part of the scorched earth policy that the Germans adopted in Tuscany as the Allies were advancing and the Germans were retreating.

When I first heard of this massacre, I was in the Tuscan town of Pontremoli, chatting with a B&B owner and her husband, about World War Two history—while on my pilgrimage.

I finally had a chance a few days ago to visit this mountain hamlet, tucked against the austere Apuan Alps—and fittingly, I visited it on Liberation Day.

Liberation Day occurred ten days after I moved to Lucca. It celebrates Italy’s liberation from the Nazis and the fascist regime. A perfect day to visit Sant’Anna di Stazzema, which is located in the province of Lucca.

I was brand new in Lucca and knew no one but I had made some local friends on Facebook and luckily they liked my proposal of visiting Sant’Anna for Liberation Day.

The road up to the hamlet is long and steep with tight curves—it is narrow and one-lane, but is used as two-lanes. As Nicola drove the little car higher and higher, I was treated to magnificent views of the wooded mountainsides giving way far below to the plains of Versilia, and to the long beaches of Viareggio and the sparkling sea.

Walking into Sant’Anna from the car park, I noticed a sign proclaiming the hamlet a National Park of Peace.

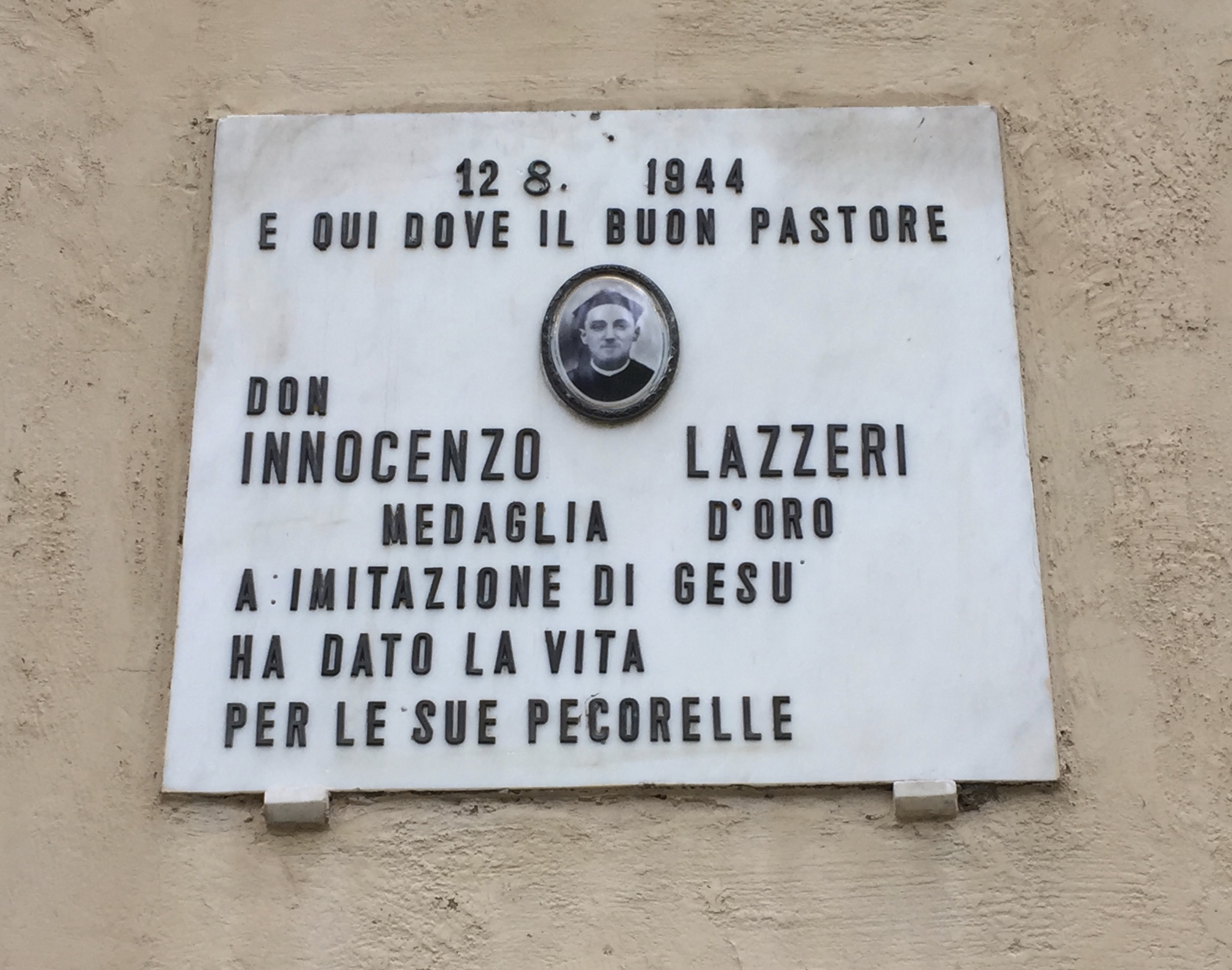

Outside the little church the first thing I saw was a plaque to Don Innocenzo Lazzeri, the 33-year-old priest who pleaded with the Germans not to kill the villagers.

His pleas were in vain. He was shot in front of the church and was later awarded a gold medal for civilian valor. Apparently his father had told him to hide and he had replied,

“No father, I can not hide, I can not abandon the population in this situation, duty requires me to present myself.”

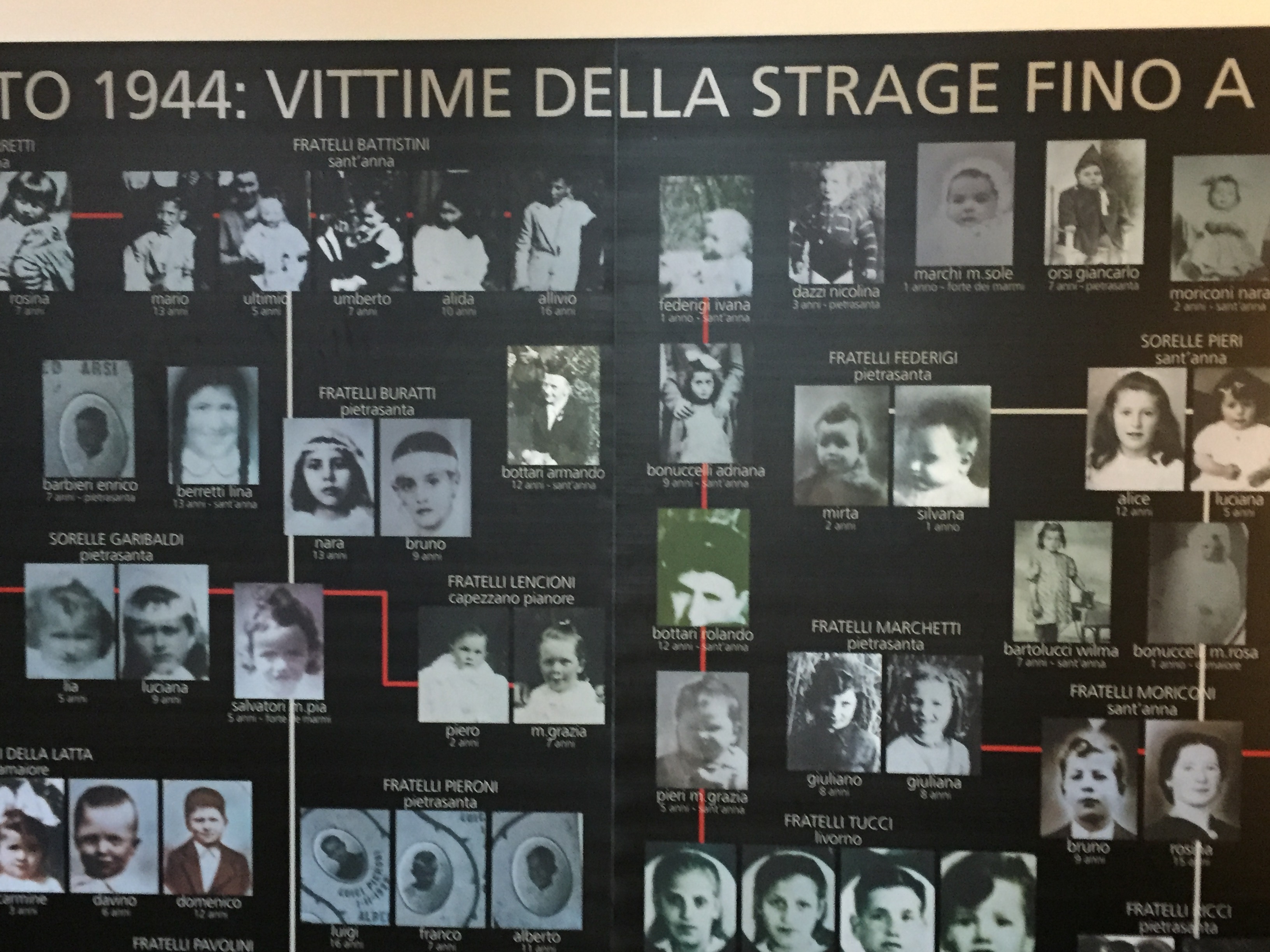

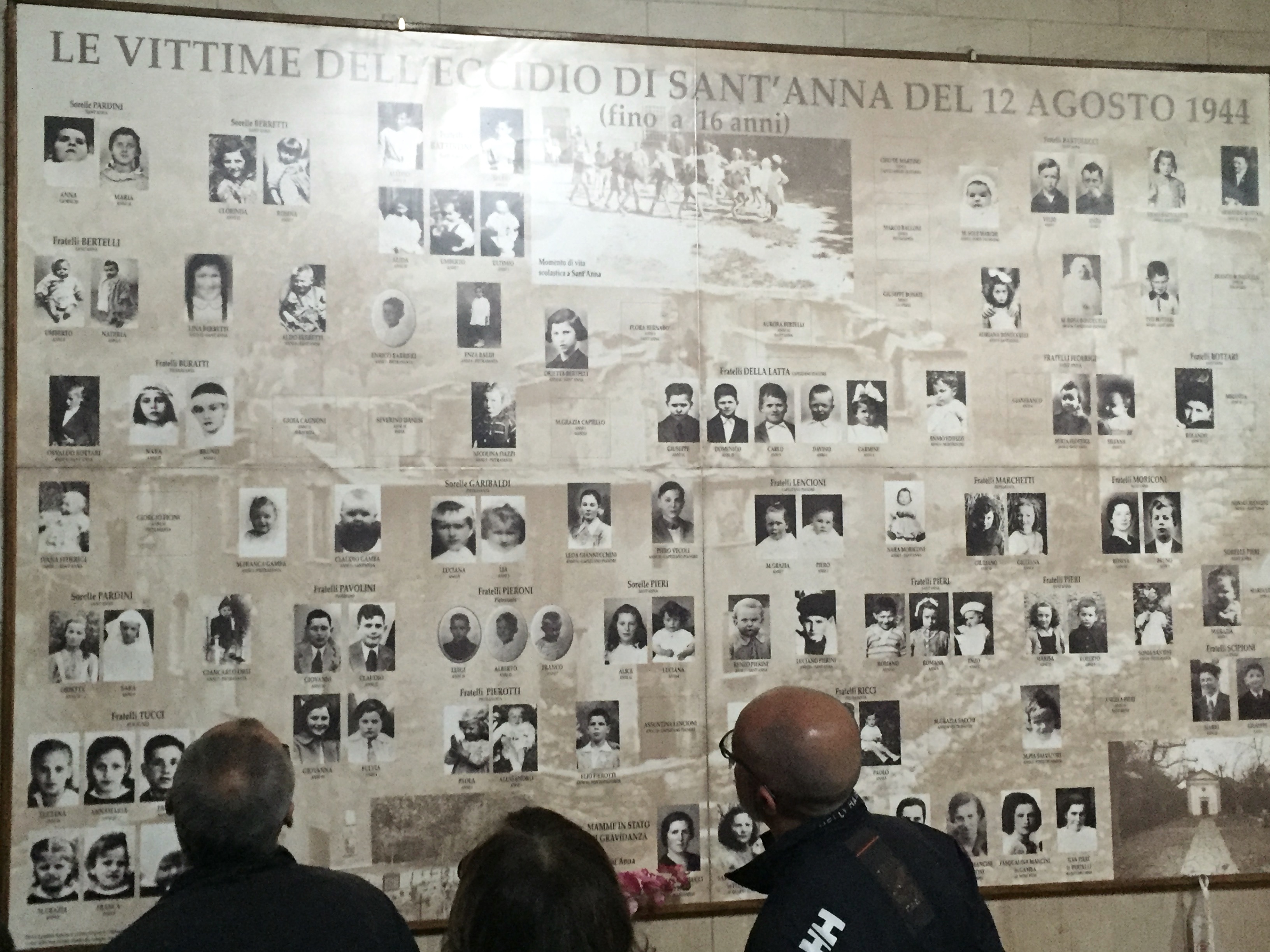

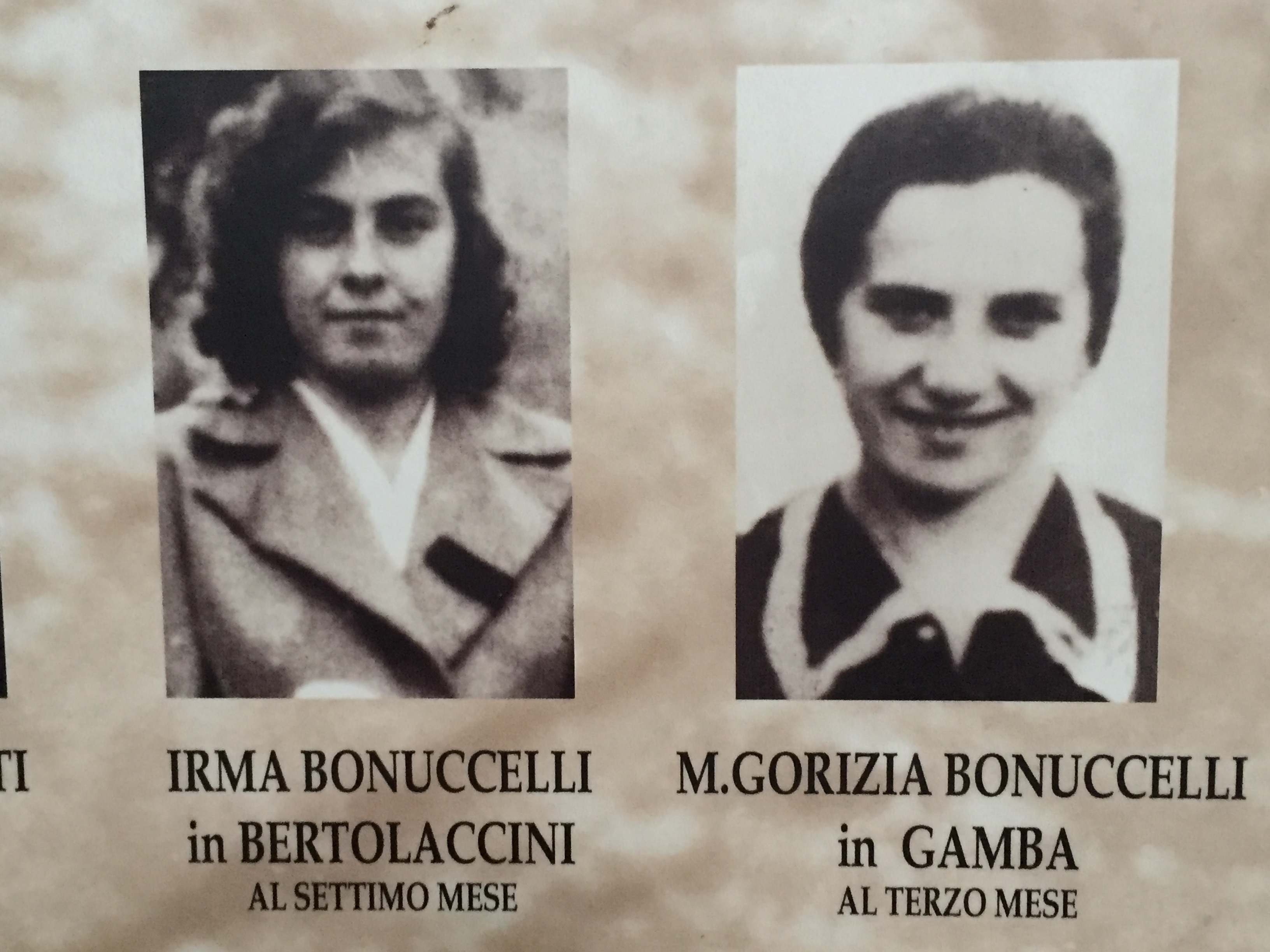

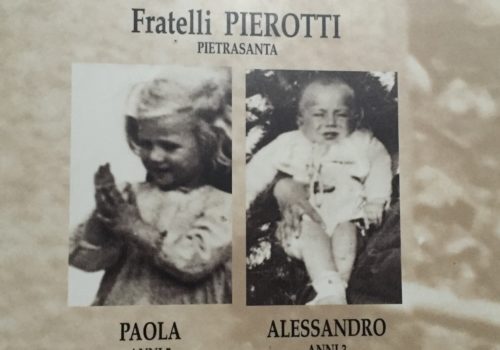

Inside the church, behind the altar, across an expanse of wall, are photographs of the victims—over a hundred children, and eight pregnant women included.

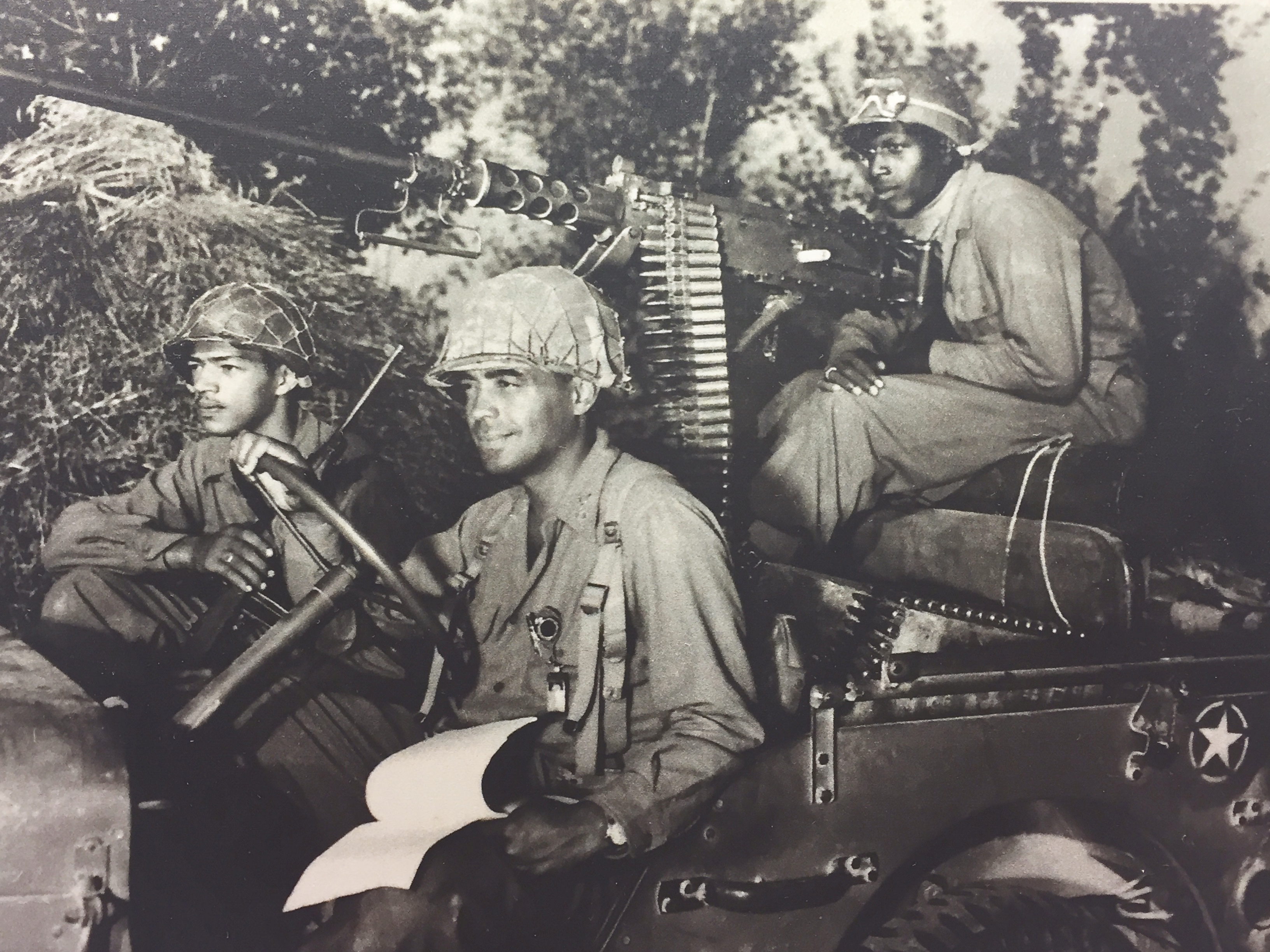

My companions and I made our way to the museum, located in what was the village school. It is a well laid out space with a video that provides an overview of the history leading up to the massacre. There are hundreds of images from the time, including one of the “Buffalo Soldiers“—a nickname given to the African American soldiers who were a segregated unit that served in the Italian Campaign from 1944 to the war’s end.

In the museum I learned that there had been no justice served for the Nazi’s crimes.

In 2005, an Italian military court found the ten members of the 16th SS “Reichsfuehrer” division responsible for the massacre and sentenced them to life in prison in absentia.

Germany however did not extradite them to Italy. In 2012, after a ten-year German investigation, the Stuttgart Public Prosecutor’s Office dropped it, citing lack of evidence.

Unfortunately the Italians only started their investigation in the 90s, after a journalist found witness statements. It is shame that after the Italian court ruling when the former Nazis were already in their 80s, the Germans then dragged on for ten years only to cite lack of evidence. This means that when the investigation was re-opened in 2014, the former Nazis were in their 90s and many had died.

In 2014, a court in Karlsruhe Germany overturned the Stuttgart decision in the case of one of the Nazis, Gerhard Sommer.

Sommer is one of the “most wanted Nazi criminals” due to his participation in the massacre at Sant’ Anna.

When the Karlsruhe court re-opened the case against Sommer, there was a glimmer of hope that justice might be served in some small way.

Those hopes were dashed when in 2015 a German court found Sommer unfit for trail because of dementia. Sommer lives in a nursing home near Hamburg.

Visit Sant’Anna di Stazzema on Liberation Day or any day except a Monday—and learn about and reflect on what the Tuscans went through in WWII.

The museum is open every day of the week except Mondays, starting at either 9:00 or 9:30—although on Sunday it may not open until the afternoon. Tuesday and Wednesday it closes at 2:00 and the other days it remains open until 5:30 or 6:00.

Oh that is so sad. Especially the part about the babies. I hate when bad things happen to little innocents. On a happier note, I love the picture of the town. Thanks for sharing!

Yes, it is shocking and unimaginable how they could have been so ruthless and heartless with these children.

Wow you have really brought to light a day in history that we celebrate annually with little awareness as to why it was such a monumental relief for so many local families. Well done!

Thanks Rupert for stopping by. Glad you liked it!

I continue to learn about another and then another city struck by Nazi killings and attacks………..

as Americans we’ve had nothing in history like this in our country yet, and of course, the younger generation in Europe can’t imagine this at all either. But these things aren’t as far in the past as they seem……..

We can only hope that tragic History taught us all something and will never be repeated

Thanks for your comment Brooke and for your thoughtfulness about the importance of learning from history.

Once again you have educated me about the history of Italy. What a precious village with such a sad history. I love seeing you with your new friends. You are so good at connecting with people Chandi. I admire your openness and curiosity.

Thanks Melisa, I guess my “connecting ability” comes from so many experiences living and traveling abroad solo.

Yes, there is always more history to learn– just in Italy a lifetime isn’t enough.

A very sad part of history. So many stories like this hidden away and yet we ALL need to remember what hate can do to innocent people. Thanks for bringing this to our attention.